Written and prepared for JRMC 8151, a graduate course at the University of Georgia

Abstract

A difficult-to-define target market and an industry used to skirting the rules: the relationship between Generation Z and the luxury fashion sector is complex – and fascinating. This literature review navigates the generational cohort theory (Goldring & Azab, 2021, p. 884-897) and the match-up effect (Song & Kim, 2020, p. 802-823) in application and how luxury brands position themselves to Gen Z (those born approximately between 1996-2012). While this review primarily focuses on studies pertaining to luxury fashion labels, there is some insight regarding high-end liquor, automobile and hospitality companies. The idea that there is a foolproof ‘formula’ is debunked, as several dilemmas are revealed throughout the research regarding the behaviors of the luxury fashion industry and the core values of Gen Z. The best suggested strategy for these brands to remain relevant to younger audiences is to walk a fine line. The balance of corporate social responsibility, mass appeal, avant-garde visuals, accessibility and social media influence is extremely finicky and delicate.

Introduction: Defining Luxury

“Sensuality, pleasure… premium quality… uniqueness, and/or innovation” or rather an identifiable brand name itself are just a few indicators of luxury in regards to a company’s reputation (Eastman, Shin & Ruhland, 2020, p. 57-60).

What is it about luxury brands that enables them to remain relevant? In the age of ‘cancel culture’ and the demand of corporate social responsibility (CSR) amongst younger audiences, how have these brands stayed afloat? Considering many of the most coveted labels in fashion can be traced back to the late 1800s, that’s a lot of room for error. No company is perfect. Everyone is bound to misstep and upset the public at some point.

The luxury goods industry tends to break the mold of universally agreed upon communications strategies. Take accessibility, for example. The Internet has connected every corner of our world to each other and to organizations through social media. While most companies insist upon taking advantage of this generally inexpensive form of organic media, luxury brands aren’t as sure. Accessibility in abundance isn’t necessarily a good thing for a brand that has carefully cultivated a reputation for being exclusive (Dobre, Milovan, Dutu, Preda & Agapie, 2021, p. 2535). Imagery, also, is a funny thing in luxury brand communications. The drive for most campaigns is mass appeal, or at least target-audience appeal, but not for highly coveted fashion labels. The high-end fashion industry isn’t afraid of utilizing artistic expression for the sake of originality and the pursuit of the avant-garde, sometimes resulting in “grotesque images” ad campaigns that “diverge from idealized conventions” (Gurzki, Schlatter & Woisetschläger, 2019, p. 403).

Summary of Findings: Gen Z Values

A 2016 survey of 297 people between the ages of 16 and 59 suggests that ‘hedonic’ attitudes toward luxury brands are present at every age, but motivation based on societal impact varies between generations (Schade, Hegner, Horstmann & Brinkman, p. 314). In fact, the psychological, hedonic function is quite powerful. While the bandwagon effect and the need for individualism are more conscious phenomena, hedonic motives are more subconscious. Purchasing luxury goods for the sake of purchasing luxury goods provides “sensory pleasure, esthetic beauty, or excitement and consequently, arousing feelings and affective states receiving personal rewards and fulfillment” (p. 316). A strong motivator for consumerism, indeed.

While certain motivations are exclusive to Gen Z’s budding relationship with luxury brands, hedonistic influences are relevant across all ages (p. 319). So if everyone has a subconscious desire for luxury, how does Gen Z differ from their parents? Unlike Gen X or Baby Boomers, Gen Z does in fact exhibit a “high level of loyalty toward luxury brands in terms of attitudes and behaviors” (Shin, Eastman & Li, 2022, p. 394). However, these loyalties are not always incredibly strong, passionate or exclusive. So, how can/do luxury brands pitch to them? Generation Z’s core motivations (regarding what constitutes an effective communication strategy) can be summarized threefold: a sense of idealism, a sense of identity, and an appreciation for beauty and innovation.

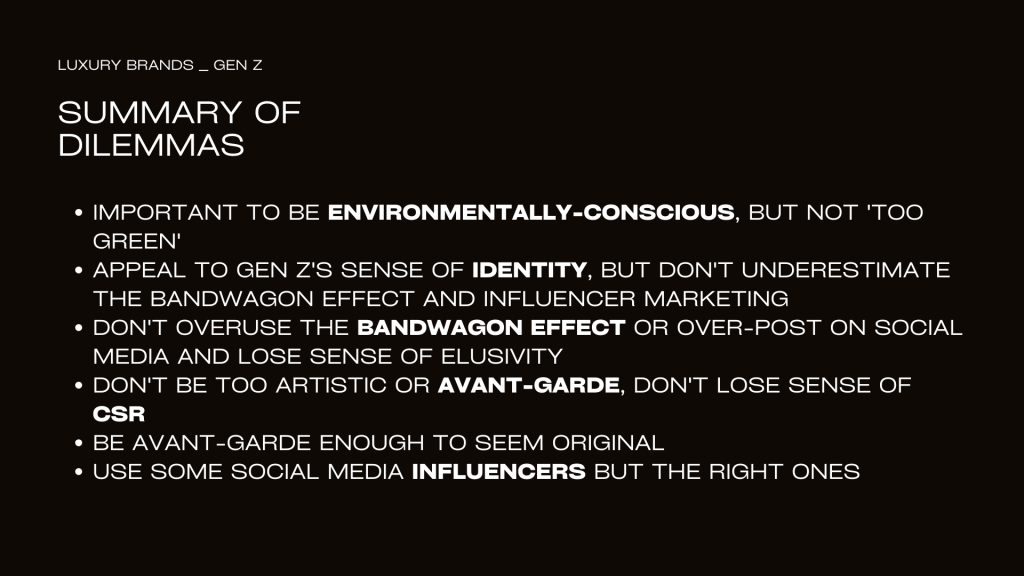

One of the defining-most traits of Gen Z is climate-change concern. A 2022 article in the 28th volume of the Journal of Marketing Communication, however, examines the rising need for corporate social responsibility (CSR) within the luxury fashion industry and one of the several dilemmas that the demand proposes: incompatibility. The study analyzes luxury brands’ communication efforts that emphasize their concern for the environment, or becoming more ‘green,’ whilst still maintaining their sense of status (Kang & Sung, p. 291). As concluded in other studies, Gen Z values environmentalism higher than any other generation and factors it in more often when making purchasing decisions. This notion, combined with Gen Z’s desire to feel not only unique– but also ethical, explains the phenomenon that the study unearths: both consumers and luxury brands tend to “engage in CSR in order to fulfill their social obligation, which further enables them to supplement their symbolic significance by creating an ethical and responsible image” (p. 294). But another question must still be asked: how much is too much? Nobody likes being pandered to by corporations. Another study, conducted in 2021, also pertains to sustainability concerns regarding luxury brand purchase motivation. The idea that luxury and eco-friendliness are incompatible is once again mentioned: luxury being “associated with pleasantness, superficiality, and ostentation,” and sustainability relating more so to “altruism, moderation, and ethics” (Kong, Witmaier & Ko, p. 640). So, is it worth it? If luxury brands rely on elusivity and Gen Z appreciates transparency, will one side of this relationship ever cave in? Both luxury brands and mass-marketed brands compete for public approval and this study focused on the fruit of their sustainability efforts. While eco-friendly messaging yielded positive brand perceptions for non-luxury brands, the luxury brands’ efforts were seen as ‘greenwashing’ and therefore not as trustworthy (p. 647). A third study attempted to determine whether or not including artwork within an advertisement will make this incompatibility appear more or less noticeable to a consumer. The ads of specific brands (Gucci, Stella McArtney, etc.) were shown to 199 United States-based interviewees and the results suggested that some eco-friendly initiatives tend to do more harm to their brand reputation than good. If brands promote their initiatives but “remain quiet about their commitment,” then sustainability efforts become associated with “greenwashing, manipulating or misleading” (Quahc, Septiano, Thaichon & Nasution, 2022, p. 2). This suggests a caveat on Gen Z’s value of sustainability: authenticity.

For a generation that has in a sense ‘seen it all’ (thanks to the Internet), originality is often rare to come by. Gen Z has a high appreciation for anything innovative: whether that be technologically speaking or artistically speaking. According to Bloomberg, more and more brands, like Dior, Gucci and Burberry are creating a Metaverse presence in Roblox and experimenting with AR and VR ‘try-on’ lenses to reach younger audiences (Ellwood, 2021). One theory that could explain Gen Z’s interest in the relationship between technology and luxury brands is their tendency to craft abstract or even avant-garde messages. A 2019 study concluded, after examining thousands of luxury and premium ad campaigns, that the core pillars are actually strikingly similar: “enrichment “(symbolism, rhetoric, and storytelling),” distancing “(temporal, spatial, social and hypothetical distance)” and abstraction “(leaving open multiple routes of interpretation)” all create a sense of ‘eye of the beholder’ likability (Gurzki, Schlatter & Woisetschläger, p. 404). This, however, reveals yet another dilemma. In a 2021 study, survey respondents were exposed to multiple CSR-intended ads and asked for their feedback– primarily, their level of confidence in the brand’s efforts to do good (Youn & Cho, p. 521). The results suggest that detailed informational ads (high content level, more text) yielded significantly more votes of confidence than ads featuring minimal, artistic or abstract content (p. 523-527). This conclusion, compared with the conclusion of the Gurzki, Schlatter & Woisetschläger study that abstract and artistic ads are generally better-received by the public, further supports the dilemma between luxury and CSR. If a company wants to convince Gen Z they can encapsulate both, there is a fine line to walk and a gray area to navigate.

The Bandwagon Effect and Influencer Marketing

All that being said, Gen Z is not impervious to common, everyday, non-subliminal persuasion. While uniqueness and maintaining a sense of identity is a major motivation for young people, the bandwagon effect is still heavily (begrudgingly) significant. The bandwagon effect is assumed to be even more powerful regarding luxury purchase motivations specifically amongst college students, who in fact “represent a vibrant segment in the luxury market” (Eastman, Shin & Ruhland, 2020, p. 56). When asked to self-evaluate “external influences on luxury consumption,” the highest scoring answer after demographics (95.2%) and income (85.7%), was indeed “interpersonal influences (79.4%)” (p. 64). This phenomenon of course is amplified by social media and it not only persuades purchase decision-making, but is also suggested to be “critical to the rise and fall of luxury goods consumption” (Cho, Kim-Vick & Yu, 2022, p. 26). While standing out in the crowd and demanding CSR are very Gen Z-esque character traits, it’s best not to underestimate the influence of peers, and of course, influencers themselves (p. 24). An ‘influencer’ is of course essentially anyone with a significant social media following and could be considered something of a tastemaker within their niche or industry. No longer simply used for spreading brand awareness, social media influencers (SMIs) are now being recruited by brands to salvage reputations (Singh, Crisafulli, Quamina & Xue, 2020, p. 465). So why use SMIs to garner trust with Gen Z? Data shows that “SMIs are able to encourage the purchase decisions of female consumers, more than celebrity endorsers” or faceless bloggers, even though celebrities and bloggers are still capable of being incredibly influential as well (p. 467). In fact, a luxury brand’s process of recruiting a celebrity endorser must be strategic in itself; “since celebrity endorsements lead to huge impacts and inappropriate celebrity selection can greatly harm brands, researchers and practitioners have focused on discovering how to select an appropriate celebrity” (Song & Kim, 2020, p. 804). What constitutes an ‘appropriate’ celebrity for Gen Z targeting? What constitutes an ‘appropriate’ celebrity in general? Song and Kim suggest the ‘match-up effect’ regarding the partnerships between celebrities and brands. They claim that even if a celebrity is “attractive, credible or likable, the celebrity endorsement can fail if there is no “fit” between the brand or product and the celebrity” (p. 804). A consumer sensing a ‘fit’ between themselves and the chosen celebrity is also crucial. It fosters a sense of self-identification between a consumer and a brand, as is crucial with Gen Z (p. 804-810).

To display the sheer volume of major ad campaigns and brand partnerships with luxury brands from 2019-2022, below is a compiled list ranging from massive celebrities to micro and macro social media influencers. There is, however, a common thread between all of these people. They are young. They are ‘likable,’ or at least relevant to younger audiences. They are controversial musicians, nostalgic former child-stars, and up-and-coming Hollywood players. They help Gen Z associate their respective brands with certain pop culture obsessions, or motifs– like the trending ‘90s/Y2K revival. Note that these ‘partnerships’ range from general ambassadorships, to sponsored Instagram posts, to wearing a designer on the red carpet, to being the face of a major multi-platform campaign.

The first category pertains to the casts of popular young adult television shows on major streaming services. Soapy, aesthetically-pleasing, coming-of-age programs. The casts are young, diverse, fresh faces and a majority of their followings consist of Generation Z:

- Cast of Netflix’s Bridgerton: Jonathan Bailey (Fendi, Omega, Ralph Lauren, Tanqueray Gin); Nicola Coughlan (Miu Miu); Phoebe Dynevor (Louis Vuitton); Simone Ashley (BMW, Gucci, Tiffany & Co.);

- Cast of HBO’s Euphoria: Angus Cloud (BMW, Ralph Lauren); Alexa Demie (Balenciaga); Barbie Ferreira (YSL Beauty); Dominic Fike (YSL); Hunter Schafer (Prada); Jacob Elordi (Burberry, Celine, Hugo Boss, YSL); Lukas Gage (Loewe, Tiffany & Co.); Maude Apatow (Fendi, Giorgio Armani, Miu Miu, YSL); Sydney Sweeney (Fendi, Giorgio Armani, Miu Miu, Tory Burch); Zendaya (Bulgari, Loewe, Valentino);

- Cast of HBO Max’s Gossip Girl: Emily Lind (Dior, Swarovski); Evan Mock (Cartier, Chanel, Givenchy, Prada, Ralph Lauren); Jordan Alexander (Fendi, Tiffany & Co., Versace x Fendi); Whitney Peak (Chanel, Moncler); Zion Moreno (Bulgari, Tod’s, YSL Beauty);

- Cast of Netflix’s Outer Banks: Chase Stokes (Don Julio, Giorgio Armani, Omega); Drew Starkey (Omega); Jonathan Davis (Four Seasons, Giorgio Armani, Hugo Boss, Moncler); Madelyn Cline (BMW, Ferragamo, Giorgio Armani); Madison Bailey (Fendi);

- Cast of Netflix’s The Society: Kathryn Newton (Hugo Boss, Ralph Lauren, Tod’s, Valentino); Kristine Froseth (Chanel, Four Seasons, Prada); Natasha Liu Bordizzo (Chanel); Olivia De Jonge (Bulgari, Gucci);

- Cast of Netflix’s Stranger Things: Finn Wolfhard (YSL); Millie Bobby Brown (Louis Vuitton); Sadie Sink (Chanel, Chopard, Givenchy Beauty, Kate Spade, Prada);

The second group consists of actors, musicians, and traditional social media influencers:

- Young Hollywood actors and former child stars: Anya Taylor-Joy (Dior); Cole Sprouse (Coach, Ralph Lauren, Versace); Daisy Edgar-Jones (Gucci, Jimmy Choo, Omega, Tiffany & Co.); Diana Silvers (Celine, Prada); Elle Fanning (Balmain, Gucci, Miu Miu, Oscar de la Renta); Emma Watson (Burberry, Prada); Florence Pugh (Tiffany & Co., Valentino); Julia Garner (Gucci, Prada, Swarovski); Kaitlyn Dever (Chanel, Fendi, Miu Miu, Rodarte); Keke Palmer (Christian Siriano, Michael Kors, Tory Burch); Kiernan Shipka (Fendi, Louis Vuitton, Miu Miu, Roger Vivier); Letitia Wright (Chanel, Prada); Lily Collins (Cartier, Ralph Lauren); Maddie Ziegler (Fendi, Kate Spade); Tom Holland (Porsche, Prada); Yara Shahidi (Cartier, Dior Beauty)

- Models, influencers and content creators: Bella Hadid (Balenciaga x Adidas, Fendi, Swarovski); Charlie D’Amelio (Prada); Emma Chamberlin (Cartier, Louis Vuitton); Hailey Bieber (Jimmy Choo, Tiffany & Co., YSL); Kaia Gerber (Celine, Loewe, Marc Jacobs, Stella McCartney); Kendall Jenner (Givenchy, Jimmy Choo, Prada); Lily-Rose Depp (Chanel)

- Rappers and pop stars: 21 Savage (Louis Vuitton x Nike); A$AP Rocky (Loewe, Mercedes-Benz); Bad Bunny (Burberry); Doja Cat (BMW, Vivienne Westwood); Dua Lipa (Alaïa, Valentino); FKA Twigs (Miu Miu); Grimes (Stella McCartney x Adidas); Harry Styles (Gucci); Jack Harlow (Givenchy); Justin Bieber (Vespa); Kid Cudi (Cadillac, Givenchy); Lady Gaga (Dom Perignon); Lil Nas X (Burberry, Coach); Megan Thee Stallion (Coach); Olivia Rodrigo (Marc Jacobs, YSL)

The Downside of the Bandwagon Effect

That being said, the bandwagon effect, while powerful, can also be dangerous to a luxury brand’s elusive and exclusive reputation. While social media is great for the average brand to access as many people as possible, a 2021 study unearthed reluctance from luxury brands to promote products or services online. The Internet is powerful. So powerful indeed, that harnessing the power of social media marketing and online retailing might “undermine the sensory experience of luxury brand consumers and that the high accessibility of the online environment, anywhere, anytime, can diminish the scarcity perception and the perceived value of luxury products” (Dobre, Milovan, Dutu, Preda & Agapie, p. 2535).

Discussion of Limitations

Since the phenomenon of social media and influencer marketing is still relatively new– in comparison to the existence of the luxury fashion industry– it should be noted that studies like these are still in an “exploratory stage” (Azemi, Ozuem, Wiid & Hobson, 2022, p. 1).

Another limitation to the selected readings is the explicit qualifications that makes a brand one of luxury or not, or lack thereof. A 2016 study involving high school students shows that definitions of and attitudes towards luxury brands can indeed shift between different countries. Overall, French teenagers are more susceptible to the allure of luxury brands and their brand loyalties to those respective brands are higher than American teenagers’ (Gentina, Shrum & Lowery, p. 5787). However for both samples, innovation yet again proves to be a strong selling point for young people, and teenagers are also burdened with the dilemma between “the value they attach to their peer groups (assimilation) and their need to emerge as unique individuals (individuation)” just like the older, collegiate members of Gen Z (p. 5789). As mentioned earlier, the definition of a ‘luxury brand’ isn’t set in stone– both operate in a gray area. Therefore, both ‘luxury’ and ‘premium’ are examined. While the Gurzki, Schalatter & Woisetschläger study defines these classifications differently, (Burberry, Hermes, Louis Vuitton and Valentino being ‘luxury’ labels and Lacoste, Michael Kors, Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren being ‘premium’ labels), it’s apparent that luxury/premium brands rely on similar techniques to communicate messages to their consumers: enrichment, distancing and abstraction (2019, p. 404).

Not only do researchers define luxury differently, respondents do as well. A 2022 study encouraged the respondents to define ‘luxury’ themselves– exhibiting evolving brand attitudes reflected in this generation (Shin, Eastman & Li, p. 398). The conductors of the study are even so bold as to say they were “mistaken” regarding some of their classifications (p. 399). This suggests a new phenomenon in the research– not only does Gen Z have a unique relationship to luxury brands compared to other generations, but they seem to define what constitutes a brand as ‘luxurious’ differently altogether.

Conclusion

All this being said, is there a foolproof formula that luxury and premium brands use to remain relevant to younger audiences? The short answer: no. As concluded in most advertising and public relations case studies, it depends. It seems that luxury brands have an extremely fine line to walk in order to be successful. ‘Successful,’ in a paradoxical sense of course, meaning highly-coveted, eco-friendly, recognizable household names, yet exclusive and elusive, but also not too mainstream or intended for the masses. It seems that as long as consumers are psychologically drawn to luxury brands and the hedonic motivations they satisfy, despite whichever generation they belong to, advertising and public relations practitioners will always have their work cut out for them.

References

Azemi, Y., Ozuem, W., Wiid, R., & Hobson, A. (2022). Luxury fashion brand customers’ perceptions of mobile marketing: Evidence of multiple communications and marketing channels. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 66, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102944

Cho, E., Kim-Vick, J., & Yu, U.-J. (2022). Unveiling motivation for luxury fashion purchase among Gen Z consumers: need for uniqueness versus bandwagon effect. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology & Education, 15(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2021.1973580

Dobre, C., Milovan, A.-M., Duțu, C., Preda, G., & Agapie, A. (2021). The Common Values of Social Media Marketing and Luxury Brands. The Millennials and Generation Z Perspective. Journal of Theoretical & Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(7), 2532–2553. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16070139

Eastman, J. K., Shin, H., & Ruhland, K. (2020). The picture of luxury: A comprehensive examination of college student consumers’ relationship with luxury brands. Psychology & Marketing, 37(1), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21280

Ellwood, M. (2021, December 9). Luxury fashion brands are already making millions in the metaverse. Bloomberg.com. Retrieved November 1, 2022, from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-09/luxury-fashion-brands-are-already-making-millions-in-the-metaverse